إجراء موس الخاص بي: ما يشبه العثور على سرطان الخلايا القاعدية وإزالته

As CEO of the Prevent Cancer Foundation, sometimes I wonder if we’re doing enough. Do people understand our message? Are we providing them with the information they need to take action? Oftentimes in health care, we forget “the people” we are trying to reach also includes ourselves.

This past May, the Foundation amplified public education messaging around Skin Cancer Awareness Month. Day after day of receiving the messages and reading our content reminding people to keep an eye on their skin and advocate for their health, it finally “clicked”—I still needed to get my skin cancer check this year. It was time for me to take action, so I picked up the phone and scheduled an appointment.

During the visit, I pointed out a very small pimple on my cheek that hadn’t yet healed. I noticed it several months ago and found it unusual that it would bleed if I rubbed the spot with a towel.

The dermatologist immediately suspected basal cell carcinoma and took a biopsy that day. I left with a small band-aid on my cheek and waited 10 days for the result. Sure enough, the spot was diagnosed as basal cell carcinoma—one of the most common types of skin cancer—and the doctor’s office recommended a Mohs procedure to remove the cancerous cells.

Unfortunately, I spent a lot of time in tanning beds in my 20s because I simply did not know or ignored the risks. The damage had been done—as evident by my recent diagnosis—but early detection made a big difference in my story. (And these days, I’m vigilant about sun safety!)

What is the Mohs procedure?

Mohs is a surgical procedure during which a doctor removes one layer of skin at a time and examines each layer under a microscope to see if any cancerous cells remain. The goal is to remove as little skin as possible while ensuring all the cancer is removed.

What is it like to have the Mohs procedure?

This is a simplified version of events based on what I wanted to know before my procedure and is not representative of everyone’s experience. For more on the Mohs procedure, check out this information from our friends at the Skin Cancer Foundation.

I arrived for my appointment at the dermatology office at 8:00 a.m. I was informed that no special preparation was required, and because they would only use a local numbing agent, I could drive myself home afterwards. I was told I’d be at the dermatology office for several hours, so I had a full breakfast that morning before heading in for the procedure.

After getting called back, I was taken to an exam room and seated in a comfortable reclining chair. No change of clothes required—I simply stayed as I was.

A board-certified dermatologist with advanced training in Mohs surgery and his assistant explained the process from start to finish, verified the location of the basal cell carcinoma and checked if I had any questions before we began.

Step 1: A numbing agent was injected by syringe into the surgical area. As many of us know from numbing for dental or other procedures, it doesn’t hurt—just a pinching feeling for a few seconds.

Step 2: The dermatologist used a spoon shaped surgical tool to scoop out the suspected cancerous tissue and a scalpel to remove the layers of skin. The goal is to remove any tissue that may be cancerous and leave you with “clear margins”—meaning tissue with no evidence of cancer. Again, I did not feel any discomfort during this process and could not see anything since I had a surgical drape around my face.

Step 3: Next up, the dermatologist brought out a tool that uses heat to stop the bleeding from the blood vessels in the surgical area. This didn’t hurt either, but the distinct smell might make your stomach turn a bit.

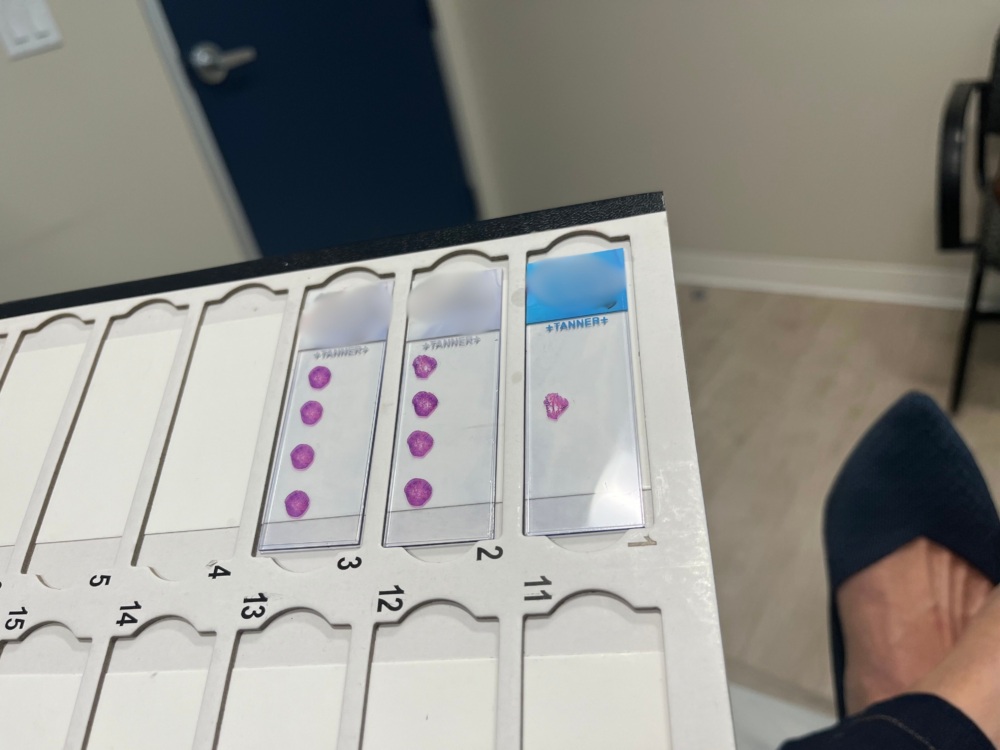

Step 4: A bandage was applied, and I was then seated in a waiting area while the layers of skin just removed from my cheek were processed and viewed under a microscope by the dermatologist to ensure no cancerous cells remained.

About 40 minutes later, I was greeted in the waiting room and given the “all clear.” Phew! If cancerous cells were still present, the dermatologist would have removed more layers of skin until no evidence of cancer could be found. This is where early detection comes into play—the longer the cancer is present, the bigger and deeper the impacted area is.

Step 5: It was time to close the surgical site. Because the area impacted on my cheek was relatively small, the best option presented was to have two layers (one internal and one external) of dissolvable stitches that would close the wound. I will have a one-inch scar, sutured as a line, to blend in with my wisdom creases (aka wrinkles) that will heal in about a year.

I was on my way back to the Prevent Cancer Foundation office at 9:30 that same morning!

I was instructed to wear a bandage on my face for seven days following the procedure. The team at dermatologist’s office reminded me several times that scar healing is a marathon, not a sprint. Other than that, I’ll be avoiding intense exercise for a few days and keeping the area protected from the sun so the scar tissue can heal properly.

The takeaway message from my experience is how important it is to point out changes or abnormalities in your skin to a dermatologist. We all have many spots on our skin and my basal cell carcinoma was the size of a pencil tip. It would have been very easy to miss—even by a professional.

And now, if I have any doubt about the impact of our work at the Prevent Cancer Foundation, I can say with certainty we are making a difference—because early detection made a difference for me.